Home

Biography

Discography

Photos

Filmography

Radio

Archives

Recordings

Labels

Sheet Music

Family

Links

Contact |

BIOGRAPHY

Virtually any phonograph owner knew the name of Billy Murray for his comical and entertaining songs he cut on record. "The Yankee Doodle Boy," "In My Merry Oldsmobile," "The Grand Old Rag," "Casey Jones," and "Alexander's Ragtime Band" all became signature songs for him. His records serve as excellent representatives of the music and events of American culture—the styles, technology, events, and popular trends. He has captured the essence and personality of the times onto record, giving a unique look into a bygone era: World War I, prohibition, the Great Depression, politics, popular trends, and so forth.

Murray's height of popularity was during the early stages of sound recording. There were no microphones used in the studios when he made his first wax cylinder records in 1897, nor during most of his career until 1925. Instead, recordings had to be done by a horn to project the sound onto a blank disc or cylinder. This was known as acoustic recording. It was used by the industry from the 1890s, until the late 1920s when most companies converted to electric recording with the microphone. Murray was a master at the process because he had all the necessary requirements in order to achieve acceptable results. His clear enunciation and distinctive style made him one of the best artists of his time. He had a unique way of making his songs come to life—delivering his material with personality and character that matched up perfectly with the subject he was singing about. |

From Ron Dethlefson's Edison Blue Amberol Recordings: 1915-1929 (Mulholland, 1999). Used with permission.

From Ron Dethlefson's Edison Blue Amberol Recordings: 1915-1929 (Mulholland, 1999). Used with permission. |

William Thomas Murray was born May 25, 1877 in Philadelphia—the same year Thomas Edison invented the phonograph. He amusingly related himself to the invention in the Edison Phonograph Monthly (January 1917):

"I squalled for the first time in 1877, and so did the phonograph. I didn't do very much for ten years after that; but neither did the phonograph. Looking back upon those days now, I can understand just why Mr. Edison did not make any attempt to improve or market the phonograph he invented in 1877 until 1887, and why it did not commence to be a commercial possibility until the latter year. I was not ready to sing for it, that's all."

Murray was the second of five children to Irish immigrants Patrick Murray and Julia Kelleher. The family moved from Philadelphia to Denver, Colorado in 1882, where Murray spent most of his childhood. A problematic child, young William exhibited overly audacious behaviors. He almost drowned a number of times, and once ran away from home at age thirteen with the intention of becoming a horserace jockey. But it was in Denver that Murray got his first exposure of the entertainment scene. At age sixteen, his parents allowed him to join Harry Leavitt's High Rollers as an actor, and afterwards continued to sing in honky-tonks, medicine shows and small-time vaudeville venues.

While in San Francisco around 1897, Murray made his first wax cylinder recordings for Peter Bacigalupi, the local Edison distributor. His first cylinder, "The Lass from the County Mayo," was a duet with his partner, tenor and yodeler Matt Keefe. Unfortunately, none of these early Bacigalupi cylinders are known to have survived, and no primary documentation on the titles and releases has surfaced.

His next major turning point came in 1902, when Murray appeared in the roster of Al G. Field's Greater Minstrels. It was here that Murray obtained the nickname of "Billy," which he would become better known as during his recording years. When the season ended in May 1903, Murray went to New York to look for work as a phonograph singer. It was during this year that Murray released his first cylinders for Edison's National Phonograph Company, "I'm Thinking of You All of de While" (#8452) and "Alec Busby, Don't Go Away" (#8453).

Library of Congress, George G. Bain Collection |

Murray would soar to great popularity during the naught years, becoming famous for comedy songs, ethnic dialects, and "coon" songs, virtually outselling any other artist. Anyone who bought his records knew whatever he did would be colorful, funny, and enjoyable. Almost anything he produced would prove to be a great seller, which is why all of the major phonograph manufacturers of the decade hired him: Edison, Victor, Columbia, Zonophone, Leeds and Catlin, American, Indestructible cylinders, and the International Record Company. It was during this time that he was coined the nickname "The Denver Nightingale" by Sam Rous, who would use it in various catalog notes and record descriptions for the Victor company.

In 1909, during the height of his popularity, Murray signed contracts to record exclusively for Victor and Edison.From 1909 to 1925, he was the lead singer of the American Quartet (also known as the Premier Quartet on Edison). In 1915, he joined a group of artists to travel throughout the country promoting the Victor Talking Machine Company. This group would become known as the Eight Popular Victor Artists, who also made the earliest electrical recording released by Victor in 1925. |

For leisure, Murray had a fondness for automobiles, and enjoyed playing and watching America's favorite pastime, baseball. As a fan of the New York Highlanders (later known as the Yankees), he played right field in their exhibition games, went to their training camp, and personally knew many of the other major players in the big leagues. Legend has it that he would call in sick on a recording date just to go out to the playoffs.

Murray renewed his Victor and Edison contracts every few years until 1919, at which point he returned to freelancing for all major record companies. The records he made during this period also proved to be good sellers, which is probably why Victor convinced him to re-sign a five-year contract with them in July of 1920. However, these would not necessarily prove to be his greatest years.

The twenties would see a new phase in the world of popular music: the Jazz Age. A wave of fresh performances by a new generation of singers would come into view. Instead of the humorous matrimonial and ethnic dialect songs that Murray was long affiliated with, the new bestselling music consisted of romantic tunes, jazz, and dance numbers. (These styles would especially become dominant in the late 1920s.) Murray continued to have steady record sales, but was making fewer and fewer solo recordings. Instead, his work was mostly confined to brief vocal refrains for dance bands, and duets with younger singers such as Aileen Stanley and Ed Smalle.

If the new musical trends weren't enough to put Murray out of the spotlight, a new technology was about to give way that would. In 1925, Victor began making commercial recordings electrically with a microphone. It was from this technology that a new, soft style of singing came in, called "crooning." The microphone was required in order to capture the soft tones of the vocalist. Gene Austin, Joe White ("The Silver Masked Tenor"), and Art Gillham were new singers who were rapidly becoming popular with this new technology, and the new musical trends to go with it.

Murray—now a longtime veteran of comedy songs approaching his fifties—did not seem to fit in well with the young picture. Although he adjusted accordingly to the new electric process, and "crooned" on occasion, his voice did not posses the same qualities as he did during his peak years. Many experts can agree that the records he made in the late 1920s do not represent him at his best. He even admitted to being more comfortable singing as he did during his traditional acoustic horn days.

Another major phase came in 1927, when Victor's president Eldrige Johnson sold his company to the New York banking houses of Speyer and Seligman. The new owners updated their artist roster with new performances, and left little room for the high-salaried artists who were long affiliated with the company. Murray was one of them, and when his last contract expired in 1928, it was not renewed. He continued to record for Victor on a freelance basis, but it appeared that his days as a bestselling artist were over. |

Ryan Barna Collection |

Murray returned to freelancing for mostly minor labels, singing solos, vocal refrains, and duets with Walter Van Brunt (known as Walter Scanlan)—another famous artist who had fallen on harder times. Murray and Scanlan also made radio broadcasts, provided voices for cartoons, and continued to make records until 1931. Throughout the 1930s, Murray made occasional 78s and played minor roles on radio dramas. He made a brief comeback on RCA's Bluebird label in 1940, and made appearances on the WLS National Barn Dance as early as 1938. His last recording session took place on February 11, 1943, when he and comedian Monroe Silver cut two parts to "Casey and Cohen in the Army" (Beacon #2001).

Murray retired in 1944 due to heart conditions. He continued to receive comeback and appearance offers, including those from Arthur Godfrey, Ed Sullivan, Decca records, and a film proposal, but they were never fulfilled.

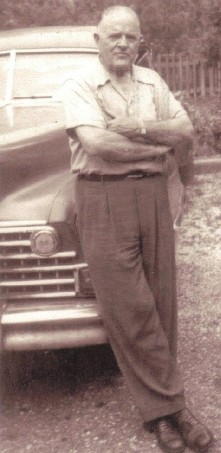

Courtesy of Howard Thain

|

His death came suddenly on Tuesday, August 17, 1954 at Marine Stadium in Jones Beach, Long Island. He and his wife with two friends decided to attend Guy Lombardo's production of "Arabian Nights." He bought his friends tickets, but then began to feel uncomfortable. He told them, "You take your tickets and go in. I'll join you in a minute. I think I will go to the lavatory." He went into the restroom, and within a few seconds, had passed away on the floor. The cause on his death certificate was given as an acute coronary thrombosis due to myocardial heart disease.

His service was held at Our Holy Redeemer Roman Catholic Church, and his burial took place at the Holy Rood Cemetery in Westbury, Long Island. He married three times—the first two ending in divorce—and produced no children, although continuing research suggests he might have been a stepfather at one time. His widow Madeline lived until November of 1986, and is buried on top of him at Holy Rood.

Today, Murray's records open a window to the past. He is now largely forgotten, primarily remembered by those who collect antique phonographs and records. His music is largely ignored (even joked) by historians due to the lack of true originality and influential values contained in them, such as classical, blues, jazz, country, and rock. Still, people loved him, and he gave the record companies what they wanted. To date, at least two CD solo albums have been issued, and his records are still heard occasionally in films and documentaries. As long as these relics are shared and preserved, the "Denver Nightingale" will continue to live on for generations to come.

|

|